International students are especially vulnerable to scams

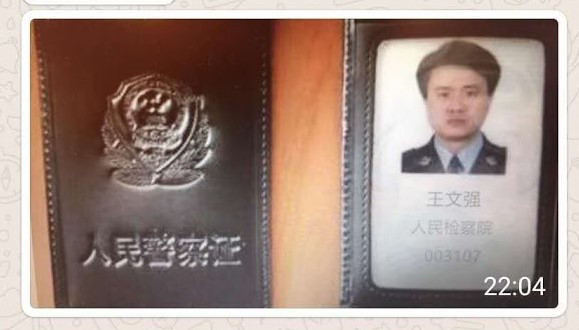

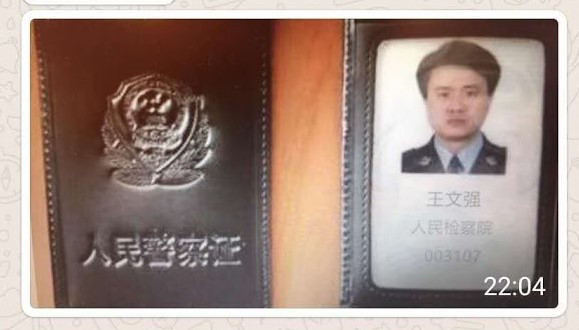

The fake police ID the scammer sent me. Photo: Yushu Tian

October 24, 2019

I nearly got swindled out of all the money in my bank account during my first week in the U.S. from a phone call. It was a lesson I want to share with others, that international students — unfamiliar with their new country and its customs — are particularly vulnerable to fraud.

One day, the phone rang at my apartment in Boston and a voice recording in English said I needed to sign for a package from DHL. For more information, I was instructed to press 9. I followed the suggestion because I had just sent my transcripts to an institution for evaluation through the DHL service. The “staff member” who answered said he worked at the Chinese Consulate and his name is “Yi Zhu.” His accent was genuine.

This “staffer,” pretending to be kind, said I may have been a victim of identity theft. “You should call the police,” he said.

My call was transferred to the “China Public Security Bureau.” I spoke with someone claiming to be a police officer in Shanghai who spoke Mandarin. He said I was suspected of money laundering and violating the laws of China and the United States. I needed to pay bail and assist in the investigation.

He sounded authentic. I immediately panicked because a few days earlier, I read on the news that nine Chinese students were sent back to China from Los Angeles for no immediate clear reason. Now, I was suspected of committing a crime and I needed to prove my innocence so I could go back to my normal school life at Northeastern University.

I was asked to hand over my personal data, including my ID, passport, Social Security and credit card numbers, for police protection.

In retrospect, scam artists would always want the same type of information to carry out identity theft and wipe off money from your bank account — your ID card, driver’s license number, passport number, Social Security card number, and credit card numbers. To gain trust, these scammers will make every effort not only to let you call back or check and verify the telephone on the Internet but also to provide police badges for verification.

But the person on the phone told me repeatedly that this matter must be kept a secret and not mentioned to others. I later realized that of course they didn’t want me to talk to my friends, university administrators, professors or parents because these people would have realized and told me that it was a scam.

The person on the phone sent me an “arrest warrant” through What’s App. I panicked some more and was eager to establish my innocence. This “police officer” said that if I wanted to clear up the crime, I needed to cooperate with the investigation because there were many people involved. Cooperation means I should let authorities check my bank account in order to prove innocence.

What happened next made me realize that it was a scam. The officer said I should send all the money in my bank account to a “public prosecutor,” whose name could not be found on the Chinese government’s website. That rang alarm bells for me. I had heard the same warning a thousand times: Only a scammer will ask people to transfer money to a strange account over the phone. I quickly hung up the phone and marked the number as “scam.” Later, I spoke with a genuine legitimate Shanghai Police officer, who said police will never prosecute anyone over the phone.

These fraudulent methods seem to be novel to me as an international student, but in fact, they are used very often in the U.S. to target vulnerable communities, the elders, college students, people who are in debt and people who are not fluent in English, like me. The scammers typically use false “arrest warrants” and “freezing warrants” to scare you into giving up your valuable information.

One in every 6 American adults lost money from a phone scam with an average loss of $244 per victim, according to a 2019 report by The Harris Poll conducted among 2,030 U.S. adults aged 18 and older.

Over half of those who have ever been scammed reported they have been a victim more than once. College graduates are twice as likely to fall victim to a scam than those with some college education or no college education, according to the report.

International students, however, are particularly vulnerable to falling for these schemes because they are not fluent in English and they get easily concerned about their visa status due to the recent climate over immigration in the U.S. Almost all the international students I have spoken with have run into scams.

The schemes can get so sophisticated that the caller ID might appear on your phone as if they are calling from the Chinese consulate or a local police station.

When I contacted the Chinese government, an official I spoke with said that the embassy and consulate will not communicate by telephone. I hope that students can learn from my story and never let anyone transfer your call to the so-called police or give out important personal information like passwords, Social Security number, bank account number.

Who to call in case of suspicious activity?

If you are a student, report it to your university police and follow their advice for follow-up actions. If you are an international student, you can also report the scam to your university’s international student office.

The Federal Trade Commission has a webpage dedicated to alerting people about the latest scams and how to recognize the warning signs. If you encounter or heard of a scam, report it to the Federal Trade Commission.