Last names have been removed to protect the privacy of those mentioned.

Many Americans heard about USAID (United States Agency for International Development) for the first time when its termination became news.

But to me, USAID was more than a headline, a government agency, a constellation of projects, or a source of funding; it was a source of hope. It was proof that when America said that it was for the people, we meant it.

When I think of USAID, I think of four-year-old Firdaus and the thousands of other refugees, children, and communities to whom we made promises to provide clean water, reliable food, education, and basic healthcare. Most of all, we promised to be there, and we may know who broke that promise, but I can’t stop thinking about what Firdaus knows: that one day we were there, saying we would do everything we could to empower her with the tools for a better life, and the next we were gone.

I met Firdaus while working with the USAID-funded Jifunze Uelewe (Learn and Understand) project, which expanded safe and inclusive education in Tanzania, with the goal of ensuring that every child could reach their full potential. The project worked extensively inside classrooms, but what stayed with me was what I saw outside, where, for children in Tanzania, most barriers to education arise. Not having clean water, food, or familial support, any one of these factors can be and often is the end of an education before it really begins. Firdaus and her classmates were pre-primary, which means an average age of four.

Understanding the weight of these barriers, the project focused on breaking them.

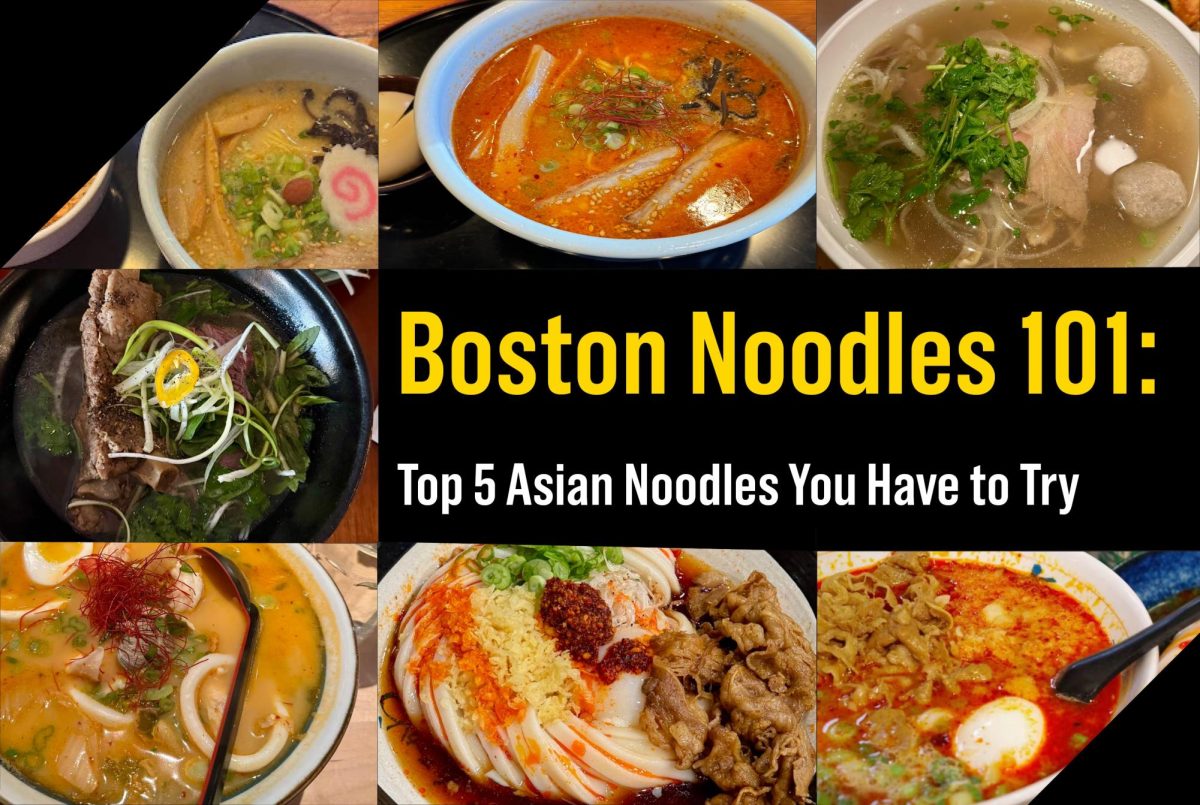

Pictured above, Firdaus and her classmates play while practicing safe handwashing while food is served through a project program that provides a substitute meal for the breakfast that most have gone without.

Smiling children are not a new image, but the joy that radiated from these little faces on that hot August morning while they enjoyed something as simple as clean water and hot food imprinted itself on me. When I felt hopeless, when I felt overwhelmed, I returned there, lingering in the reminder of all that I had to be grateful for.

2025 took that away. When I look at these photos now, I feel sick, a mixture of dread and guilt twisting my insides with the knowledge that just as we may have brought that joy, potential, and promise, we have now taken it away.

I’ve spent my career in humanitarian aid, specifically USAID-funded work, and was one of the thousands who watched as their professional universe dissolved this year. As the spring blurred into summer, and the reality set in that all the democratic checks and balances would do nothing to check this one man and his desire to destroy everything we’d spent decades building, I began to grieve in a way that was darker and more isolating than anything I could have imagined. Imagine losing not just your job, but also your professional universe, virtually overnight, and for no reason. Even our samples of work, project records, and any trace of achievement had evaporated, taken offline along with the digital universe that once outlined USAID’s global efforts. We hadn’t just been eliminated; we had been erased.

I was angry, but far deeper was the sadness, for every Firdaus, and for every American.

While my work in the field resembled photojournalism, my title was communications. That meant that it was my job to ensure that no matter where this work happened globally, it would be understood, as “From the American People.” Now, I could not stop the sinking dread that all those decades and dollars spent to ensure that people knew that America cared would only solidify the certainty of the opposite.

I never considered myself a patriot, and perhaps for that reason, I underestimated how core to my sense of self the tenets I thought this country stood for—empathy, solidarity, fighting for the underdog—were, until they vanished and I found myself on unstable ground. Worse still, that ground was an island. USAID’s universe was nuanced and my role, niche. Explaining my profession was always time-consuming and would now be punctuated by tears. I could not stomach the thought of justifying why I was devastated while being devastated. On the rare instance that I attempted to explain my grief, I was typically met with a few words: “It’s just politics.”

This didn’t feel like politics. This felt like a basic right, violated. Like careers built by people who just wanted to help people, destroyed. Like decades devoted to cultivating trust globally, erased. Worse still, this reaction to all of it, this felt like exactly what he wanted. He wanted us to be revolted enough to turn away. In the blind spot this created, he could continue to inflict pain, without consequence.

In addition to Firdaus, my thoughts since those dark spring days have also remained with Daniel. One of thousands of project staff whose livelihoods had also vanished without warning, Daniel had spent the last few years working closely with my team as the Jifunze Uelewe project’s Communications Manager. From him, I learned about Tanzanian culture, specifically, how USAID was helping his country to grow.

“So many jobs are lost,” said Daniel when I reached out. I knew he was supporting a family of five and that it would be impossible for him to find another job like this. I think I also wanted to say, as irrelevant as it seemed now, that someone in America still cared.

His account broke a piece of me that I did not know was still together. While I seethed over the injustice, Daniel was resolute in his gratitude to the American people for changing so many lives. I do not know why I was surprised. Our field staff were accustomed to working in instability, unrest, and doing so with compassion and humility. Somehow, this reaction only magnified the scale of the injustice. No one deserved this, but especially not them.

“I’m proud of what we were able to do,” he said when pressed for his feelings. “We were empowering a generation of Tanzanian children…I’m proud that we were able to show everyone what they were capable of if they had the tools they needed. I hope one day this work can continue.”

I could not find the words to respond to Daniel at first. I liked him too much to lie and also too much to say anything that felt truthful. Finally, when the weight of the silence began to feel like it was answering for me, I replied with the only thing that felt honest, but also humane, “I hope so too, Daniel. I hope so too.”