Analysis: How did China eliminate COVID-19 so quickly?

People have dinner in a hot pot restaurant as usual in China Featured Photo by Yunjia Hou Oct.7,2020. Photo credit: Yunjia Hou

December 1, 2020

Life in China has returned to normal. But it took measures by a strong central government that probably would not work in many democratic countries, where politicians must be careful not to offend voters and worry about civil rights.

But in China, people don’t need to work from home and students can get back to campus. Restaurants, supermarkets and movie theaters have been fully reopened. Although masks and temperature tests are still required when taking public transportation in big cities like Beijing, buses and subways are full as usual.

Tourism is back. I toured Mount Huangshan, China’s Anhui Province at the end of August. The “sea of people” impressed me more than the sea of clouds on the mountain.

a famous tourist attraction in China’s Anhui Province, August 22, 2020.

Photo credit: Yunjia Hou

Our National Day holiday really saw the uptick in tourism. Tourist attractions across China received a total of 637 million visits during the National Day and Mid-Autumn Festival holiday from Oct 1 to 8, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism said on Oct 8.

The figure was 79% of the visits made during the same holiday last year on a comparable basis.

Even hospitals, the places we were afraid to visit most during the pandemic, have people waiting in lines now. I visited a dentist on Sept. 21 and it didn’t seem that people in the hospital were concerned about catching the virus.

Life in China has truly returned to normal while many countries are still suffering from the pandemic. How China was able to defeat the coronavirus so quickly?

I think the reasons are complex because the coronavirus crisis is not only a public health issue but a complex political, economic and social problem.

As a Chinese student who studied in the U.S. for two years and returned to China this August, I have seen both the U.S. and China’s efforts to fight the pandemic. I know some measures that work in China will not work in many countries.

But it’s interesting to learn about China as a country through the coronavirus crisis and some lessons from China can be possibly applied to other countries to combat the pandemic.

Strong leadership and strict policies

The crucial part of fighting against the virus in China was stopping the virus in Hubei Province, especially in the city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19. Due to strong leadership, the Chinese central government was able to mobilize all sorts of resources from all over the country.

According to China’s National Health Commission, over 42,000 medical workers were sent to Hubei Province. In terms of medical supplies, Wuhan can either take supplies from other hospitals or can easily order them from factories, because most hospitals in China are public hospitals and the central government authorized Wuhan to mobilize public medical resources across the country.

To avoid too many medical resources flooding into Wuhan while other parts of Hubei Province suffered shortage, the National Health Commission worked so that 19 provinces and municipalities were paired to assist with 16 cities and counties in Hubei Province, outside Wuhan. For example, east China’s Jiangsu Province gave assistance to the city of Xiaogan, the second biggest hotspot of COVID-19 in Hubei Province.

Apart from mobilizing medical resources, China has implemented strict quarantine policies around the country, especially in Wuhan.

In Wuhan, flights, trains and buses leaving the city were canceled, highways out of the city were blocked and all intra-city public transports suspended during the 76-day quarantine. Residents who were infected with the virus were forced into quarantine at a hospital.

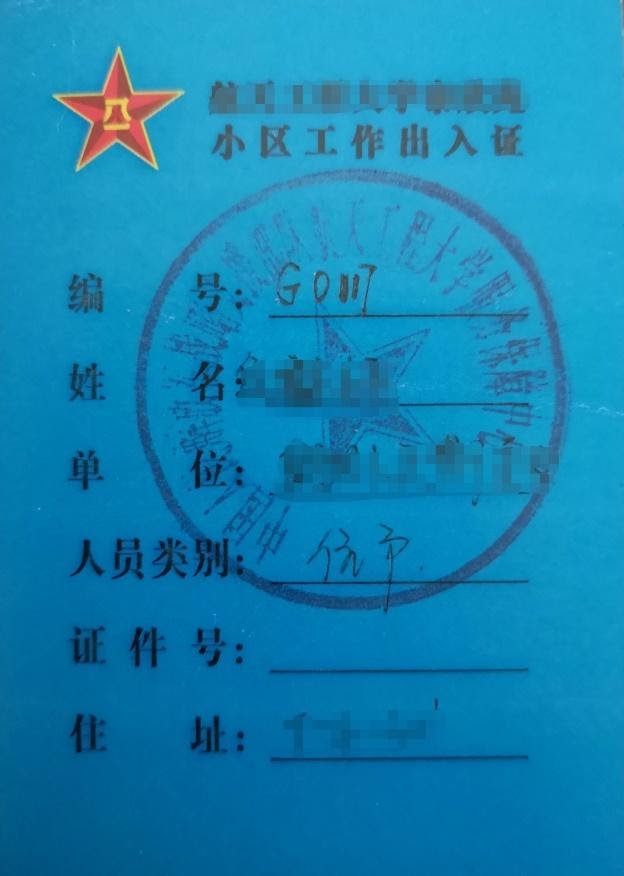

In Wuhan and big cities like Beijing, people had to wait in a long line outside a supermarket to get their temperature checked before being allowed to enter. When entering or leaving a residential compound, which usually holds 10 to 20 apartment buildings, residents were required to show their compound passes to the guard.

Photo credit: Yunjia Hou

My family lives at an apartment in Haidian District, Beijing. My father said during February and March when the virus was not totally under control, residents who went to work could leave or enter our compound with the pass every day, but residents who didn’t go to work, like retired people and housewives, could only leave the compound twice a day to busy essentials within a two-hour limit.

Later, China started using health QR code, a smartphone app, to track people’s movements. The codes have three colors. Green means a person is healthy and safe to travel. Amber and red mean a person will be barred from entry. People need to present their QR codes when entering public places such as shopping malls, hospitals and banks. The policies in different provinces are a little different.

my name, my ID number and the valid time range of this code.

Photo credit: Yunjia Hou

As the coronavirus has been almost eliminated in China, more and more places don’t check health QR codes when you enter.

I know some of these policies would not work in other countries. The strict quarantine and tracking policies might anger some people who felt they hurt their civil rights and privacy. Also, in democratic countries, officials don’t like to offend voters and lose their votes. The way Chinese central government was able to mobilize huge resources would be impractical in other countries, where resources are private.

But in the end, China successfully defeated the pandemic.

Through early October, three-quarters of China’s COVID-19 cases have been in Hubei Province, unlike that the virus has spread to every corner of the U.S. China’s death toll so far is about 4,700 and confirmed cases are 91,000. Those numbers are obviously smaller than many countries. Wuhan, the once epicenter of COVID-19, ended its lockdown on April 8, and life had returned to normal for the rest of China earlier. However, in many countries, they are still not sure whether they can control the virus by the end of 2020.

When I was in Boston early this year, I was sad and angry seeing the tragedy in Wuhan happen again and again in U.S. cities, from New York City to Miami, Los Angeles, and then to Houston. The policies in China may be too harsh to some degree, but many measures in the U.S. are too inefficient.

Supportive citizens in a collectivism culture

Many western publications have written about how China defeated coronavirus quickly, but I feel most of them missed a crucial factor — Chinese people supported policies like masks wearing, social distance and self-isolation.

People in Asian countries like Japan, South Korea and Vietnam are also supportive of those virus-control policies.

But the same policies have been opposed by many western residents. In the U.S., some people believe the coronavirus is a lie, question mask wearing, and demand reopening the economy, even though the pandemic is still severe.

Why are Asians more supportive? Because their personalities are more obedient than western people? Or they have limited ways to argue policymaking with their governments? There may be something to that.

But I think the deeper reason is we grow up in a collectivist culture. We will feel very sorry and even guilty if we break the virus-control rules and spread the virus to people around us.

Take myself as an example: although I’m pretty healthy and I believe I can survive the coronavirus, I didn’t leave my apartment unless necessary when I was in Boston. I had two roommates and I didn’t want to increase their risk of catching the virus.

If they were ill, their parents in China would be upset. Even if they recovered quickly I would feel bad about them going to the hospital, paying for treatment and being quarantined at home. I would feel worse if they suffered long-term effects and they were mad at me. Additionally, it would be a shame if my parents and friends knew that I didn’t take the virus-control seriously and spread the virus to my roommates.

That’s the collectivist culture I mean among Chinese people. It is in our education and we grow up with it.

When I was in elementary school, if I was late for a big group activity, I would feel ashamed. Not only because I made the whole class wait for me, but also made my class fall behind other classes. Punctuality is a good trait and my lateness would make my class seem not as good as other classes.

In other words, Chinese people value group interest more than people in many other countries. We think it’s acceptable to hurt individual interest a little bit to protect the group interest.

Oct.7,2020. Photo credit: Yunjia Hou

That’s why people in Wuhan were generally supportive of the strict lockdown policies. They lived 76 days uncomfortably, in exchange for knowing they helped the country’s well being in the long run. And that’s why my roommates and I stopped doing outdoor activities to protect our health and interest as a unit.

I’m not saying individual interests are not important. Nobody likes his or her interest to be violated. But when it comes to a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, when problems cannot be solved in regular ways, sometimes individuals must bend to protect the long-term interests of the group.