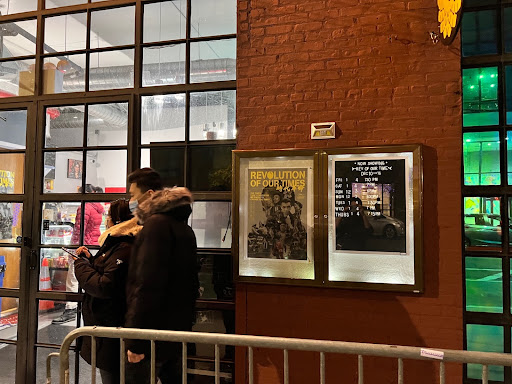

Stuart Cinema & Cafe in Brooklyn, NY, one of the locations screening “Revolution of Our Times.” Photo by Lausky

Controversial documentary on Hong Kong protests airs in U.S.

A documentary about Hong Kong’s 2019 pro-democracy protests hit the big screen in multiple cities on Dec. 11, making the U.S. the first country to show the controversial film, after its debut in a few film festivals.

The documentary, “Revolution of Our Times,” directed by Hong Kong filmmaker Kiwi Chow, chronicles the social turbulence in Hong Kong which started in June 2019 with street-level details. It is now showing in major cities including New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C. Tickets have been selling out quickly.

“Although many scenes I have seen before, the trauma is still here when I am looking back systematically today,” said a woman, who called herself Hongkonger, after watching the film. She currently lives in New York, but flew back to her birthplace to join rallies and demonstrations after the movement began. As others interviewed, she used either an alias or first name to protect their safety.

The film was a last-minute addition to the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. The organizer did not notify any participants before the debut to avoid enraging Beijing, given its long history of film censorship and constant clashes with different film festivals.

Earlier this year, Beijing censored Chinese director Chloé Zhao’s Oscar-winning movie “Nomadland” after discovering comments she had made previously that described China as a place “where there are lies everywhere.”

Dividing the year-long tear, gas-versus-Molotov cocktail battle into nine chapters, the 2½-hour documentary features a handful of protesters, including hardcore vigilantes, school-age first responders, web-savvy organizers, septuagenarian advocates, students and journalists. Many appear in the film with their appearances blurred or hidden.

The film also underlines several significant events during the movement, including the June 16 protest that garnered over 2 million participants, and ended with the 12-day siege of Polytechnic University. An 18-year-old student protester shot by police, the July 21 Yuen Long attack and the Aug. 31 MTR station incident were all also featured.

“It is touching, reminding me of things that happened in the past few years with many details,” said a man, who asked to be named Duckie because of personal safety concerns. “There are many memories and experiences included in this film.”

As a Hongkongese-American, Duckie jokingly called himself one of the film actors because he went back to the embattled city and joined the protest as a frontline black-clad protestor.

“I already started crying when I saw the first few scenes of 2 million people on the street,” said Hongkonger. “The story that touched me the most is the last few scenes about an 11-year-old kid who went to the protest frontline, which broke me down and made me unable to stop crying.”

Chow took the film title from the latter half of a popular protest slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times,” first created by now-imprisoned student-activist Edward Leung in 2016. It has been widely used since the anti-extradition law movement sparked.

After Beijing imposed the sweeping National Security Law last year, it is now considered illegal to chant or display the slogan in public space. Government officials said the slogan implies Hong Kong’s independence and subversion of state power.

To avoid potential repercussions under the law, Chow produced the film clandestinely for two years to ensure he could complete it without harassment. Apart from himself, all of the crew’s credits are listed by nicknames, partial names or pseudonyms to protect their identities. He insisted on attaching his full name because he believed the film was lawful and saw it as a way to oppose self-censorship. However, he stated that the documentary was made “by Hongkongers.”

“The film does not make me feel disappointed, but it is similar to the documentaries, movies and video segments I watched before which all of them are unable to deliver a complete story, but only show one aspect,” said Eddie, a man from Hong Kong and works in New York’s catering industry.

“From a political standpoint, there are a lot of missing narratives that deserve to be explored,” he said. “But the film does not reach my expectations of telling a more complete story to present on the world stage.”

Last month, the film was awarded the best documentary at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards. This film festival is dubbed the Chinese-language “Oscars” but has been banned from broadcasting in China because it has featured Chow’s previous work.

Accepting the award in a pre-recorded video speech, Chow said he wished to dedicate the film to “Hongkongers who have a conscience, justice and who have cried for Hong Kong.” He previously told the South China Morning Post that the film would not be screened in Hong Kong because he did not want to put his interviewees, co-workers and cinema operators in danger of retaliation.

The 42-year-old Hong Kong native is best known as the co-director of the dystopian anthology of five stories called “Ten Years,” which won the best picture at the city’s top film awards. Released in 2015, the Black Mirror-like film imagined the circumstances of Hong Kong after further encroachment by China in 2025.

Chow was accused of breaking coronavirus restrictions after police raided a private film screening held by a district councilor in August. According to the regulation, the rules do not apply to private gatherings.

He later sold the documentary to a European distributor and deleted his copies of the footage to protect himself from potential legal backlash. Although his friends had suggested that he leave the city over his sensitive work, he decided to stay because he did not want to be trapped by fear.

In October, Hong Kong’s legislature passed a new censorship law against films that “endorse, support, glorify, encourage and incite activities that might endanger national security.” Carrie Lam, the chief executive of Hong Kong, said the changes were necessary because the city’s film inspectors had no concept of national security before the National Security Law was implemented.

“Some of these individual rights and freedoms have to be restrained by law in order to have a civilized society,” Lam said. “Is it that easy to step on these red lines and thereby stifle freedom of expression in Hong Kong’s creative industry? I firmly believe it won’t.”

Chow revealed that he was mentally prepared to be arrested. The film ends with a note acknowledging that some of the people featured have later been arrested.

“No matter what role you played in the movement, no matter if you were in the frontline or backup, there is no way for us to forget the hurts,” Hongkonger said while choking up. “The only thing we can do is to use the trauma as a channel to continue our roles, no matter if you are in Hong Kong or overseas countries.”